Summary of Findings

Strand 1 - Parameters

Strand 1 investigates aspects of voice identification which are yet to be fully tested within the current voice parade procedure (e.g. length of samples, number of foil voices, witness instructions, parade type), aiming to modify the procedure to optimise earwitness performance.

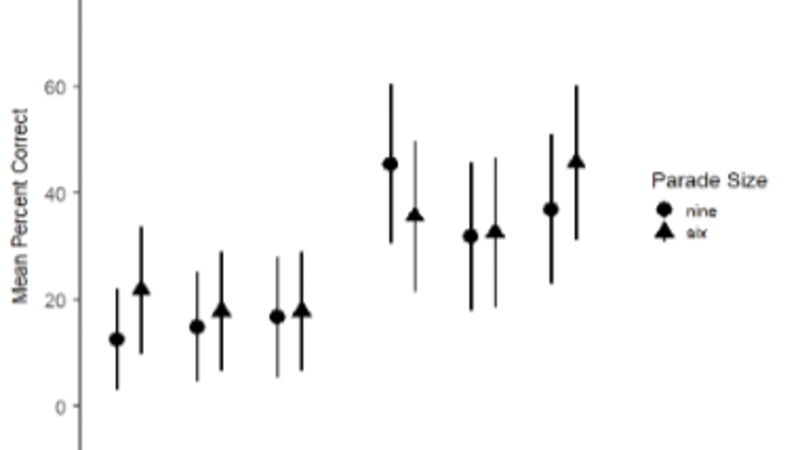

Experiment 1 investigated the effect of parade sample duration (15s, 30s or 60s) on voice recognition accuracy. The current Home Office guidelines recommend using samples of 60s, however, constructing samples of this length from interview tapes can be time-consuming. We wanted to test whether sample duration might be reduced without undermining earwitness performance. 270 participants listened to a voice sample featuring a ‘perpetrator’, then after a delay they were asked to identify the ‘perpetrator’ from a 9-person voice parade if the perpetrator was present. Participants either undertook a parade where the perpetrator was present to simulate a guilty suspect having been apprehended, or they completed a parade where the perpetrator was absent to simulate an innocent suspect having been apprehended.

Performance was better for the target-present parades than the target-absent parades. Although descriptively the 15s sample resulted in more accurate performance overall, the effect of sample length on accuracy was not found to be statistically significant.

Our results provide initial and tentative evidence which supports reducing the length of voice samples in a voice parade, but not the number of voices. Reducing the sample duration, but not the total number of voices, would still make identity parade construction significantly less resource-demanding.

Results from Strand 1 have been presented at SARMAC 2021, BPS Cognitive Psychology Section 2021, IAFPA 2021, Cambridge Language Sciences ECR Symposium 2021, NTU Showcase 2021 (see outputs).

Strand 2 - Voice Distinctiveness

The second strand investigates why it is that certain speakers are more distinctive-sounding than others from a phonetic perspective, and whether speakers judged to be more distinctive are also more memorable. We conducted an experiment in which listeners were asked to rate the similarity or dissimilarity on a nine-point scale of pairs of voices in different accent groups. We measured a range of different phonetic features (e.g. pitch, resonances, speaking rate) for each speaker and examined correlations between the listeners’ similarity judgements and the speakers’ different phonetic features to assess which features are the most important for perceptual similarity. This experiment found complex patterns both within and between accent groups, with pitch and resonances playing important roles. Results from this study were presented at AISV in February 2021, and also at the IAFPA and UK Language Variation and Change (UKLVC) conferences during the summer of 2021 (see outputs). Further work considering the effect of the duration of samples in making judgements of voice similarity is underway.

Strand 3 - Social Stereotypes

The third strand examines how social perceptions, judgements, attitudes and stereotypes related to voice(s) could potentially motivate witness decision-making during voice parades. We are investigating the evaluative judgements made about speakers based solely on their voice. We know from previous research that some voices are perceived as sounding ‘more criminal’ than others, and that some speakers may be seen as more likely to commit certain crimes than others.

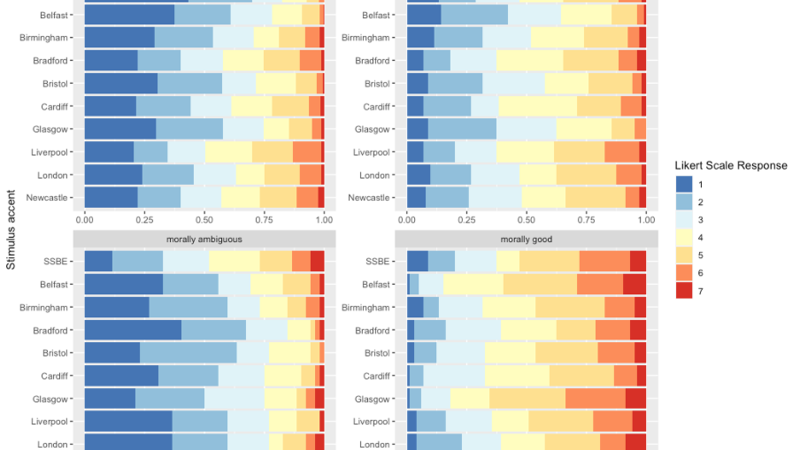

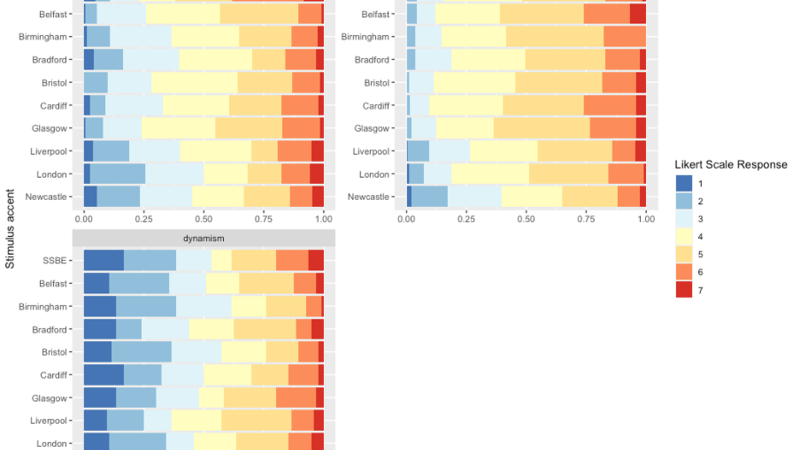

We prepared voice samples from 10 UK accents and asked listeners to rate these voices on social attributes broadly categorised as dimensions of ‘status’ (e.g. intelligence, richness), ‘solidarity’ (e.g. friendliness, trustworthiness) or ‘dynamism’ (e.g. confidence) - borrowing from sociolinguistic research. We also asked participants to rate whether the speakers would be likely to commit certain crime types (e.g. shoplifting, physical assault) as well as other non-criminal behaviours (e.g. infidelity, returning a lost wallet). Responses were collected in the form of Likert scale ratings where 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. 100 listeners completed either the social attributes ratings or the behavioural ratings.

Non-England accents (Glasgow, Belfast, Cardiff) performed well on solidarity dimensions, being rated highest on morally good behaviours and lowest on morally bad behaviours. Northern English and London accents were rated lowest on status dimensions and were rated most likely to commit crimes overall. Specifically, vandalism, physical assault and theft were considered more likely for Northern English accents. These results inform us about attitudes and prejudices about accents that could be brought by earwitnesses or juries to voice line-ups and courtrooms.

Results from Strand 3 have been presented at BAAL 2021, IAFPA 2021 and UKLVC 2021 (see outputs).

Strand 4 - Legal Interaction

Strand 4 aims to assess and evaluate the extent of police and legal practitioners' awareness and experience of voice parades, beliefs about earwitness memory, attitudes to conducting voice parades and how earwitness evidence is received in court. A successful webinar was held on 11th November where Kirsty McDougall and Jeremy Robson discussed the legal and practical issues with voice identification and admitting it in court.

We are currently conducting a survey of legal practitioners to learn about their experience of earwitness evidence in the legal context. Please follow this link to the survey, which is short and completely anonymous, and will help us with our research.

We are also conducting interviews with police professionals to learn more about their awareness and experience of earwitness evidence in law enforcement. If you are a police professional and would be interested in participating, please contact Jeremy Robson in the first instance, who will pass your details on for interview at a later date.